There’s plenty of art that speaks to nature’s beauty. But how many artists actually fight for nature itself, carving the record of that struggle into their work? This week, we introduce artist Hélène McNicoll, who transforms life’s profound trajectory into art. Her story reads like a compelling narrative in itself—leaving behind 53 years of family legacy to pursue the path of an artist at 59, chasing freedom, life’s most precious value. Her work goes beyond simple visual beauty, awakening us once again to our forgotten bond with the natural world through deep resonance.

Ecological Art’s Contemporary Context

McNicoll’s practice emerges from a rich tradition of ecological art that extends far beyond the Land Art movement of the 1960s and 1970s. Unlike early Environmental art, ecological art involves functional ecological systems-restoration, as well as socially engaged, activist, community-based interventions. Her work positions itself firmly within this activist tradition, where art becomes a vehicle for environmental advocacy rather than mere aesthetic contemplation.

The Material Revolution of Fiber Art

Her choice of recycled textile fibers places her work within another significant art historical trajectory. It was only during the Bauhaus years in the early 20th century that textiles began to enter the vocabulary of modern art. Modern fiber art takes its context from the textile arts, which have been practiced globally for millennia, yet McNicoll’s approach represents something distinctly contemporary. By using materials rejected by industrial textile production, she challenges both the hierarchies that separate craft from fine art and the waste cycles of modern manufacturing.

McNicoll’s art cannot be discussed separately from her life. Before becoming an artist, she was part of a family business operating the beautiful nature park “Canyon Sainte-Anne” outside Quebec City. She wasn’t just a manager. She was a guardian of nature who fought to have the park’s riverside designated as a conservation area to preserve its natural environment.

“I had to fight to get the riverside of the park designated as a conservation area. My art stems from this struggle. I have a special vision of being able to access quality nature while being a city dweller.”

A year before COVID, she reached a major turning point in life by selling the park to the local community, deciding to realize her long-held dream of becoming an artist. She enrolled in Laval University’s visual arts program at 59 and was even able to study in France.

Though her life circumstances changed, past experiences remain closely connected to the present. The essence of her struggle to protect nature continues unchanged, just in the new form of an artist. The joy of creation she felt as a child making things in her carpenter father’s workshop and her fundamental nature of “needing to move her hands” naturally led her to three-dimensional sculptural work using recycled textiles.

Material as Memory

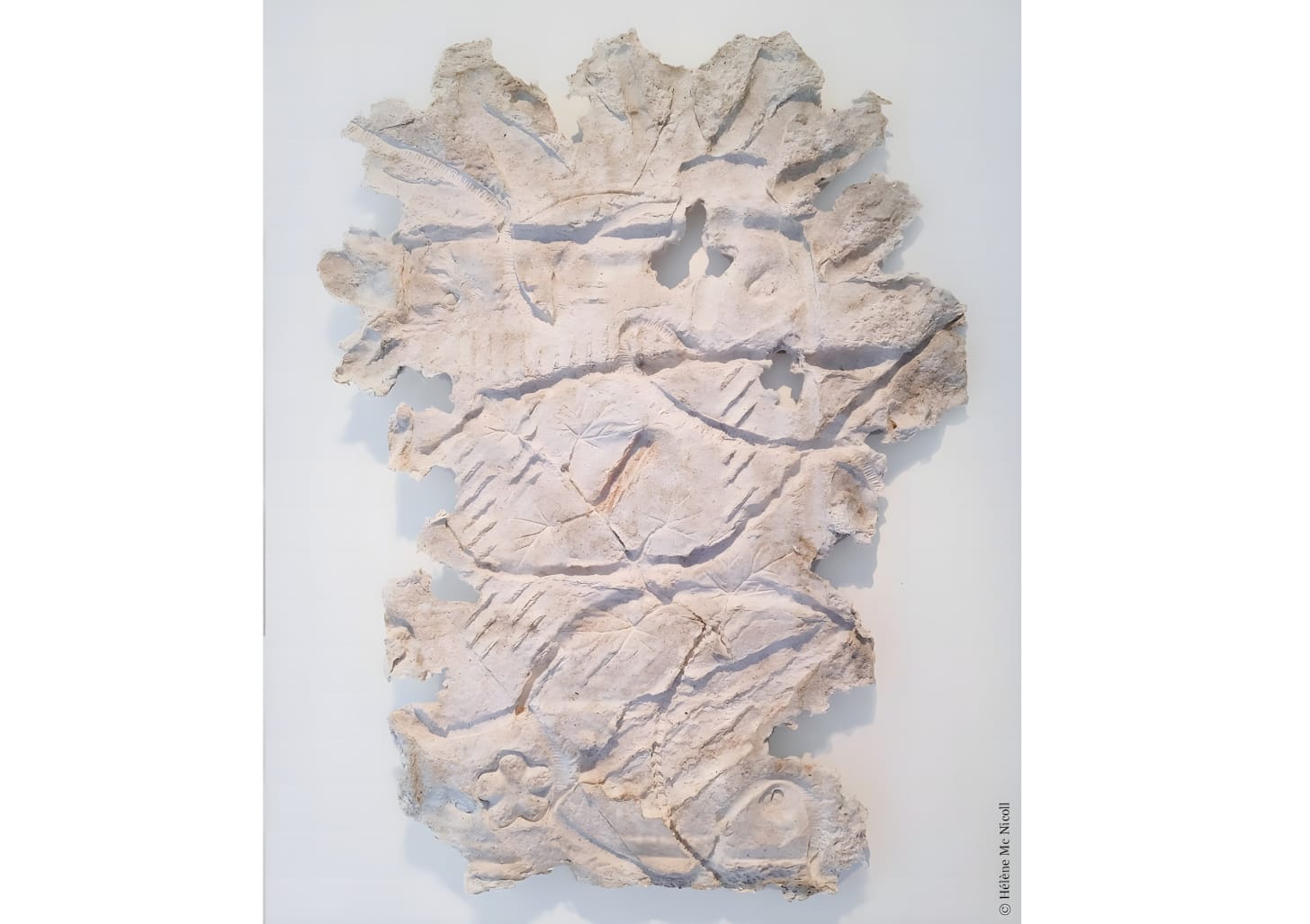

Her artistic language weaves together life’s struggles and beliefs directly. Recycled cotton fibers discarded because they couldn’t be made into fabric become rough-textured surfaces that capture the world’s traces in her hands. Through extensive research, she developed her own technique for using textile fibers as sculptural materials, incorporating her longing and affection to connect with trees as vibrant nature into her work. This material choice is not merely aesthetic—it’s archaeological, preserving the industrial refuse of our throwaway culture while transforming it into vessels for environmental memory.

This artistic exploration can be examined through two main series. The first, “By my Tree,” personifies specific trees in threatened urban forests as historical figures. “By my Tree Murray” (2022) recreates the texture of red spruce bark using rough abaca and cotton fibers. The work’s dark red colors and entwining forms simultaneously evoke General Murray’s military uniform and the scars of war, visualizing the memories of a tree that holds historical tragedy. Like a discarded military jacket, the piece drapes with the weight of both natural and human history, its red-streaked surface suggesting wounds that refuse to heal.

In contrast, “By my Tree Chilly” (2022) uses mud from the St. Lawrence River and pear tree as materials, appearing like weathered clothing worn by the land’s indigenous people or long-time residents. The rough forms created from natural materials and fibers draped like a ceremonial garment make us feel the warmth and weight of a being’s life. The piece’s earth-toned palette and organic textures speak to cycles of habitation and abandonment that cities rarely acknowledge.

Her recent work “Inter-Sections Blue” (2025) represents the culmination of this exploration. Within fragments like blue geological strata, traces of plants, animals (birds), and human industry (grid patterns) coexist. But the white silhouettes of birds flying freely through all that oppression and boundaries leave a powerful impression, clearly showing the hope and dynamic energy of life that remains unbroken in any situation. The work operates like a compressed timeline where industrial development, natural cycles, and resistance movements occupy the same visual field.

Beyond Romantic Environmentalism

The social significance of her work extends beyond simple nature advocacy to probe the mechanics of ecological disruption. In our digitally mediated world, she places deeper value on direct human encounters that begin with face-to-face meetings and shared experiences. This philosophy extends to her approach to nature as well.

For her, trees aren’t just part of nature, but the closest companions she’s observed throughout her entire life and precious beings that must be protected. What she seeks to convey through art is an expression of urgent need to restore authentic exchanges between humans and humans, and between humans and nature.

“For me, recognizing the value of an individual tree’s life means recognizing the precious connection that exists between humans and other living beings. I want to ignite awareness of the fact that we are all connected to each other.”

Currently, she teaches drawing to young people and gives lectures on health and nature, maintaining close connections with her local community. The relationships formed through her past work in tourism and her current membership in “Engramme,” a printmaking art center, are all precious assets connecting past to present. Ironically, her biggest challenge is also making her unique artistic world known to broader regions through direct connections with people. Her struggle to protect Quebec’s nature continues now in the form of an artist.

She always welcomes collaboration with people who appreciate the meaning of her work, and recently had the special experience of creating a piece for Quebec’s Coop des 2 Rives funeral home. Through work completed while respecting grief and diverse beliefs, she gained confidence that her art can deeply engage with public spaces.

McNicoll’s work serves as sincere testimony to life and poses profound questions to all of us living in fragmented times. As an artistic craftsperson recognized by the Conseil des Métiers d’art du Québec, she will continue to offer us inspiration and time for reflection on the true meaning of relationships through works that honestly incorporate her life. We recommend that you try to communicate directly through her website https://helenemcnicoll.ca/ or her Instagram.